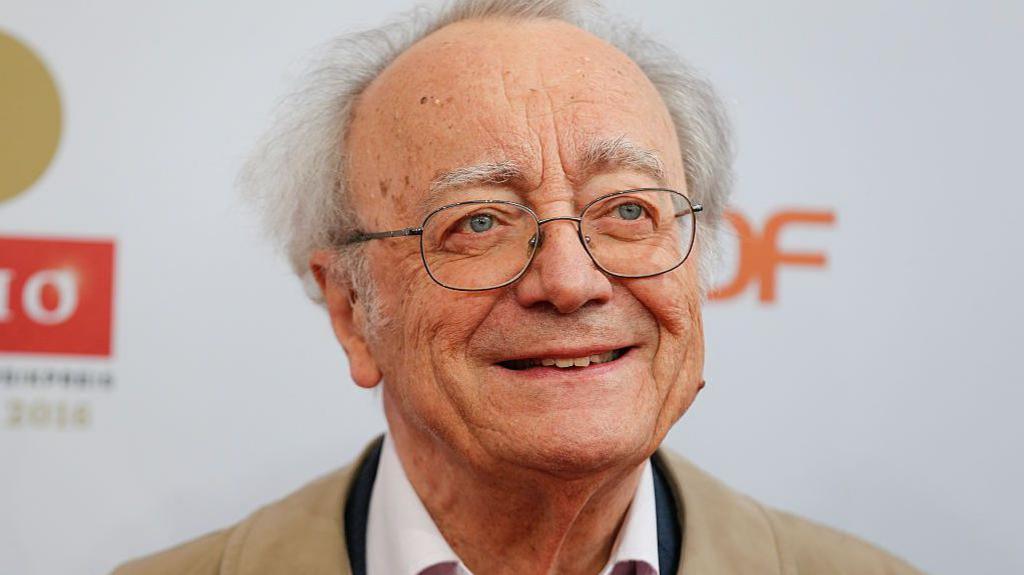

Alfred Brendel, the distinguished Austrian pianist who passed away at 94, was known for his dual persona—part erudite musician, part whimsical observer of life. Often mistaken for comedian Woody Allen due to his puckish face and eccentric demeanor, Brendel embraced absurdity, humor, and intellectual precision, qualities that shaped both his performances and writings. He once cited “laughing” as his favorite pastime, reflecting the deep paradox of his personality—reverent artistry laced with irreverent wit.

Brendel’s performances, particularly of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, earned him global reverence over a career spanning six decades. Though known for academic rigor and discipline, his music never lacked soul or whimsy. He championed composers like Schoenberg early on and might have delved into contemporary music if it hadn’t risked compromising his devotion to the classical canon. His ability to merge intellect with deep emotion was the hallmark of his artistry.

Brendel retired in 2008 after a year-long concert tour, with his final recital in Vienna featuring Mozart’s youthful Piano Concerto No. 9. His penultimate London recital in 2008 was a testament to his mature artistry: while some vigor had diminished, his interpretive nuance was unmatched. His selection of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert highlighted the composers closest to his heart, while encore performances nodded to the broader breadth of his musical interests.

An Independent Path Shaped Brendel’s Artistic Identity, Intellectual Depth, and Beethoven Mastery

Born in Moravia (now in the Czech Republic), Brendel had an itinerant childhood, moving frequently due to his father’s varied professions. His musical education began in Zagreb and later continued in Graz, Austria. Remarkably, he received relatively little formal instruction, something he believed was an advantage—it fostered independence and self-criticism. This unorthodox path laid the foundation for his intellectual, original approach to music-making.

Brendel’s first public recital at 17 was a bold statement of individuality: a program entirely made up of fugues by Bach, Brahms, Liszt, and himself. His interests extended to painting and literature, even exhibiting his artwork alongside performances. Participation in masterclasses with Paul Baumgartner, Eduard Steuermann, and Edwin Fischer further honed his artistry. These experiences, combined with his innate curiosity, shaped a musician unlike any other.

A cornerstone of Brendel’s career was his deep commitment to Beethoven. He was the first to record the composer’s complete piano works and undertook several monumental sonata cycles across Europe and America. While some early spontaneity gave way to spiritual depth in later interpretations, his Beethoven remained authoritative. His recordings, especially those with Philips and later reissued by Decca, solidified his place as one of the definitive Beethoven interpreters.

Brendel Balanced Intellect and Emotion in Music, Writing, Performance, and Personal Expression

Brendel’s writings reveal his intricate understanding of Mozart, whom he portrayed as balanced between irony and intimacy, neither saccharine nor aloof. His Mozart was vital, rhythmic, and emotionally clear. Schubert, by contrast, he approached as music teetering on the edge of despair and transcendence. Brendel viewed Schubert’s moods as proto-romantic, often dark and visionary, requiring a performer to walk a psychological tightrope.

Brendel’s approach to Liszt highlighted the music’s structural fragmentation and mystical qualities. He believed the interpreter’s role was to bridge silences and transitions with sensitivity. Despite his cerebral reputation, Brendel conveyed the transcendental essence of Liszt’s works like Vallée d’Obermann with powerful intimacy. Even when technical prowess waned in later years due to physical issues, his philosophical depth and emotional insight only grew more pronounced.

Beyond solo repertoire, Brendel recorded extensively with leading conductors and singers, including Simon Rattle, Neville Marriner, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. His writings—Musical Thoughts & Afterthoughts, Music Sounded Out, and Music, Sense and Nonsense—demonstrated his scholarly and critical acumen. His poetry books revealed his love for absurdity and surreal humor, often exploring eccentric scenarios rooted in music and human folly.

Even after retiring from performance, Brendel remained active as a lecturer, often critical of historical performance excesses. He valued authenticity as a balance between fidelity and expression, not dogmatic adherence to tempo or phrasing. Offstage, his passions included architecture, literature, and collecting kitsch. Married twice and a father of four, Brendel’s legacy is that of a singular artist who fused intellect, humor, and profound musical truth, forever resisting easy categorization.